Health Benefits of Probiotic Foods and Supplements

Health Benefits of Probiotic Foods and Supplements: The Ultimate Evidence-Based Guide

Reviewed by Dr. Maya Hernandez, MD, MPH (Preventive Medicine)

Probiotics are one of the few nutrition topics where enthusiasm and confusion rise at the same speed. One headline says they transform gut health, mood, immunity, and metabolism. Another says most products are overhyped and barely different from placebo. Both views contain part of the truth, but neither is complete enough to guide real decisions.

At their best, probiotic foods and supplements are practical tools that can support specific outcomes in specific people. At their worst, they become expensive routines with vague promises and no measurable benefit. The difference is not usually whether probiotics are "good" or "bad." The difference is whether the strain, dose, timing, and clinical context match the goal.

This guide gives you a clear, research-grounded framework to use probiotics intelligently in 2026. You will learn where evidence is strongest, where it is still mixed, how probiotic foods differ from capsules, how to avoid common buying mistakes, and how to build a food-first gut routine that does not depend on marketing claims. If you want additional background before diving in, these related site guides are useful companions: health benefits of probiotics, probiotic strains and species research, immune-supportive probiotic foods, nutrition for a stronger immune system, and good bacteria and probiotic fundamentals.

TL;DR: Probiotics are strain-specific tools, not universal cures. Food-first habits plus targeted supplements beat random "high CFU" shopping almost every time.

Can Probiotic Foods and Supplements Really Improve Gut Health?

Yes, they can, but the effect is not automatic. The modern definition of probiotics requires live microorganisms that provide a health benefit when consumed in adequate amounts (FAO/WHO, 2002; ISAPP consensus, 2014). That definition sounds simple, but it carries four hidden rules that matter in real life: the microbes must be alive at intake, the dose must be sufficient, the strain identity must be clear, and the benefit must be linked to that specific strain in a relevant population.

This explains why some people feel better quickly while others notice nothing. Two products can both say "probiotic" and still differ in strain evidence, stability, and survival through storage and digestion. It also explains why probiotic yogurt can help one person with antibiotic-associated symptoms while a random multi-strain capsule does little for another person with chronic bloating.

The practical frame is simple: probiotics can support digestive resilience, but they are not a replacement for fiber intake, hydration, sleep, medication adherence, or diagnosis of underlying disease. Think of probiotics as one layer in gut-care strategy, not the whole strategy.

Trillions of Gut Microbes Influence More Than Digestion

Your gut microbiome participates in digestion, intestinal barrier integrity, immune signaling, and production of short-chain fatty acids from fermentable fibers. That does not mean every gut symptom is a "microbiome problem," but it does mean microbial balance can influence how your body handles diet changes, stress, infections, and medications.

In clinical guidance, this is why probiotics are discussed as condition-specific interventions rather than broad wellness cures. The American Gastroenterological Association guideline and technical review emphasize that evidence quality and benefit size vary by condition, and some use cases are stronger than others (Gastroenterology, 2020).

| Microbiome function | What it does | Why probiotics might help | Limits to remember |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digestive fermentation | Breaks down fibers and produces metabolites | Some strains can support gut ecosystem stability | Low-fiber eating patterns can blunt benefits |

| Barrier support | Helps maintain intestinal lining function | Specific strains may improve tolerance after disruptions | Not a substitute for treating infections or inflammation |

| Immune interaction | Trains and modulates immune responses | Some evidence supports reduced infection burden in select groups | Effects are strain- and population-dependent |

| Motility and symptom pattern | Can influence gas, stool pattern, and comfort | Certain probiotic combinations may ease IBS symptom severity | Symptom relief is often modest, not curative |

Probiotic Foods vs Supplements: Same Goal, Different Use Cases

People often ask whether food or capsules are "better." The more useful question is what each option does best. Probiotic foods deliver live cultures in a dietary context that also includes protein, minerals, and fermentation byproducts. Supplements provide a concentrated, standardized dose that can be easier to test for targeted outcomes.

Food-based intake works well for long-term routine building, especially when tolerated foods are consumed consistently. Supplements are often more practical for short-term protocol-style use, such as when a clinician recommends a specific strain during or after antibiotic exposure. Many people benefit from combining both approaches: food as baseline, supplement as a time-limited tool.

| Option | Strengths | Tradeoffs | Best use case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fermented foods | Whole-food nutrition, habit-friendly, culinary variety | Live culture counts can vary; not all products are truly live | Daily maintenance and dietary diversity |

| Single-strain supplements | Precise strain targeting and easier dose tracking | Can be expensive and may not fit every symptom pattern | Condition-specific short trial with defined goal |

| Multi-strain supplements | Potential broader coverage in some protocols | Harder to know which strain is driving effect | When backed by trial evidence for that exact blend |

| Synbiotic-style food + supplement plan | Supports microbes with both organisms and fermentable substrate | Requires better planning and symptom tracking | People aiming for sustainable gut routine changes |

A common mistake is assuming high CFU equals high effectiveness. Dose matters, but strain quality, viability through shelf life, and evidence fit matter more. A lower-dose strain with strong condition-specific evidence can outperform a high-dose product with weak relevance.

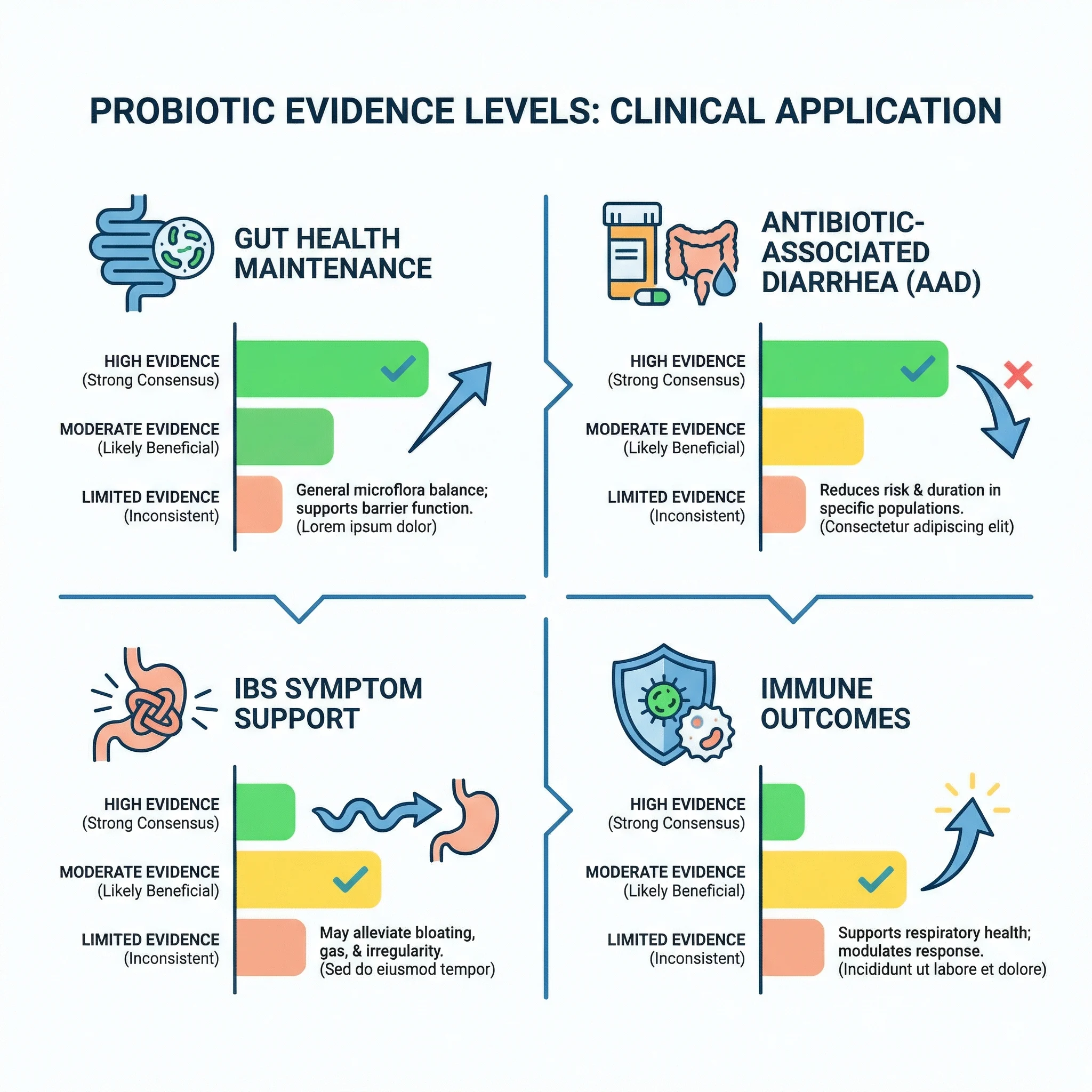

Which Health Benefits Have the Strongest Evidence in 2026?

The most defensible probiotic benefits are still targeted, not universal. Based on guideline-level and systematic review evidence, the strongest use case remains prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in selected populations. A large Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis reported meaningful risk reduction in children when appropriate probiotics were used with antibiotics (Cochrane, 2021).

For irritable bowel syndrome, the evidence is supportive but heterogeneous. Multiple recent meta-analyses suggest that some probiotic interventions can improve symptom severity, especially abdominal pain and bloating, yet effect size differs by strain and study quality. A 2024 meta-analysis in Clinical Nutrition ESPEN reported overall symptom benefit trends while reinforcing the strain-specific nature of outcomes.

Immune and respiratory outcomes show a "possible benefit" signal in select cohorts, not a blanket guarantee. A 2025 individual-participant-data meta-analysis in Frontiers in Immunology found that one specific strain was associated with reduced common cold-like symptom burden in healthy adults, which is promising but not generalizable to every probiotic label.

For inflammatory bowel disease, severe chronic GI disease, or complex immune conditions, probiotics should be treated as adjunctive and clinician-guided. In these settings, stronger decisions usually come from combining evidence, diagnosis, medications, diet pattern, and lab trends rather than trying to solve everything with an over-the-counter product.

Myth vs Fact: What Probiotics Can and Cannot Do

Most probiotic disappointment comes from mismatched expectations. If you expect a single capsule to erase years of low-fiber eating, chronic stress, and irregular sleep, almost any product will feel ineffective. If you use probiotics as a targeted tool with measurable goals, the odds of meaningful benefit increase.

| Myth | Fact | Practical move |

|---|---|---|

| "All probiotics work the same way." | Benefits are strain- and condition-specific. | Choose products with evidence for your exact goal. |

| "Higher CFU always means better outcomes." | Dose matters, but evidence fit and viability matter more. | Prioritize proven strain identity over marketing numbers. |

| "If I eat yogurt, I do not need fiber." | Microbes need fermentable substrates to thrive. | Pair probiotic intake with fiber-rich plant foods. |

| "Probiotics can replace medical treatment." | They are adjuncts, not substitutes, for diagnosed disease care. | Use with clinician guidance when symptoms are persistent. |

| "If I do not feel better in two days, it failed." | Some outcomes need several weeks and better baseline habits. | Run a structured 4-8 week trial with tracking. |

A Busy Week, Antibiotics, and the Most Common Gut Reset Mistake

Imagine a common scenario: someone takes antibiotics for a sinus infection, feels temporary gut disruption, then buys a random probiotic with the largest CFU claim online. They use it for five days, feel only slight change, and conclude probiotics do not work. This outcome is common, but it reflects poor protocol design more than probiotic failure.

A better protocol is straightforward. Start with a specific goal, such as reducing antibiotic-associated digestive symptoms. Use a product with human evidence in that context. Stay consistent for a clinically reasonable window. Track stool pattern, bloating, abdominal pain, and tolerance. Keep hydration and fermentable fiber intake steady. Reassess after the planned trial window instead of changing products every few days.

This approach does not guarantee success, but it creates an interpretable test. In evidence-based nutrition, good decision design often matters as much as the intervention itself.

How Do You Pick a Probiotic Supplement That Is More Likely to Work?

Most labels provide too much marketing and too little decision-critical information. You need a short checklist that filters noise fast. Look for full strain naming, viable count through shelf life, storage instructions, and a published trial trail that matches your intended use.

| Label check | What good looks like | Why it matters | Red flag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strain identity | Genus, species, and strain code listed | Evidence is tied to exact strains | Only generic names without strain code |

| CFU transparency | Guaranteed at end of shelf life | Viability at consumption is what counts | CFU listed only "at manufacture" |

| Storage integrity | Clear temperature and handling guidance | Heat and humidity can reduce live counts | No storage guidance at all |

| Clinical relevance | Human studies for your target use case | Improves probability of meaningful effect | Only animal or in vitro claims |

| Quality testing | Third-party quality or contamination controls | Supports label confidence and safety | Opaque sourcing and no verification |

One more practical rule: avoid stacking multiple new supplements at once. If you change three variables together, you will not know what helped, what caused side effects, or what was neutral. Single-variable testing produces better health decisions than aggressive stack building.

Food-First Gut Strategy You Can Sustain for Months

If your goal is long-term gut resilience, food consistency is usually more powerful than supplement rotation. Fermented foods can provide regular exposure to live cultures while also improving meal quality and adherence. The key is tolerable, repeatable intake, not perfect eating.

A practical weekly pattern can look like this:

- Add one probiotic food daily in a consistent serving you tolerate well.

- Pair it with prebiotic-rich plants such as oats, legumes, onions, garlic, asparagus, or bananas.

- Keep hydration and meal timing stable to reduce confounding symptoms.

- Increase variety gradually instead of introducing multiple fermented foods in one day.

- Track symptoms and stool pattern for four weeks before deciding whether to add a supplement.

This structure reduces the "all or nothing" cycle where people overcorrect for a week and then quit. The highest-return plan is usually boring and consistent: moderate diversity, stable routine, and periodic reassessment.

Who Should Be Careful With Probiotics?

Probiotics are generally well tolerated in healthy people, but not risk-free in every context. Federal health resources note that people with significant immune compromise, severe illness, central venous catheters, or major underlying medical complexity should discuss probiotic use with clinicians first (NCCIH; NIH ODS). In higher-risk settings, rare bloodstream infections linked to probiotic organisms have been reported, which is why medical context matters.

You should also pause and get clinical input if you have persistent GI bleeding, unexplained weight loss, prolonged fever, new severe abdominal pain, or chronic diarrhea that does not improve. These are diagnostic signals, not supplement problems to self-manage indefinitely.

For everyone else, the risk profile is usually manageable when products are chosen carefully, stored correctly, and used with realistic expectations. Mild gas or temporary bloating can occur early in some people and often settles as intake is adjusted.

A 6-Week Probiotic Trial Plan Beats Guesswork

If you want better results, test probiotics like a structured intervention instead of an impulse purchase. Most people stop too early, change brands too fast, or mix several new products at once. That makes outcomes impossible to interpret. A simple trial framework improves decision quality and reduces wasted spending.

Start by choosing one target symptom. It can be stool consistency after antibiotics, fewer bloating days, lower cramping frequency, or fewer disrupted workdays due to GI discomfort. Then choose one product with strain-level evidence for that goal, and avoid changing your diet pattern dramatically during the first few weeks.

| Trial phase | Timeline | What to do | Decision checkpoint |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Days 1-7 | Track symptoms without adding a new supplement | Set realistic starting point |

| Initiation | Weeks 2-3 | Introduce one probiotic product at labeled dose | Watch early tolerance and adherence |

| Stabilization | Weeks 4-5 | Keep dosing, meals, and hydration consistent | Look for trend, not day-to-day noise |

| Evaluation | Week 6 | Compare baseline against current symptom pattern | Continue, adjust, or discontinue |

This method does not make probiotics magically effective, but it gives you a fair test. If there is no meaningful improvement by the end of a well-run trial, switch strategy instead of escalating dose blindly. In prevention and digestive health, disciplined iteration beats supplement optimism.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long should I try a probiotic before deciding if it works?

For many goals, a structured 4-8 week trial is reasonable. Shorter windows can miss slower symptom shifts, while longer use without tracking can become expensive guesswork.

Should I take probiotics during antibiotics or after finishing them?

Some protocols use probiotics during and after antibiotic courses for prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. The right timing depends on strain, indication, and your clinician's guidance.

Are refrigerated probiotics always better than shelf-stable versions?

Not always. Stability depends on formulation. What matters is verified viability through shelf life under the storage conditions listed by the manufacturer.

Can probiotic foods replace supplements completely?

Sometimes yes for general maintenance, but not always for condition-specific targets where a studied strain and standardized dose are needed. Food-first and targeted supplements can work together.

Do probiotics help with bloating right away?

Some people notice early changes, but many need a few weeks and supportive habits such as fiber balance, hydration, and meal regularity before results become clear.

The Bottom Line: Use Probiotics Like a Strategy, Not a Trend

Probiotic foods and supplements can support health, but their value depends on precision and consistency. The strongest outcomes come from matching strain to goal, building a food-first baseline, and using supplements as time-limited, measurable tools.

If your current approach is random product switching, simplify. Pick one evidence-aligned target, define a clear trial window, and track meaningful outcomes. That shift alone usually improves results more than buying another "maximum strength" label.

Sources

- FAO/WHO. Guidelines for the Evaluation of Probiotics in Food (2002).

- Hill C et al. ISAPP consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic (Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2014).

- National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Probiotics: Usefulness and Safety.

- NIH Office of Dietary Supplements. Probiotics Fact Sheet for Health Professionals.

- Su GL et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Role of Probiotics in the Management of Gastrointestinal Disorders (Gastroenterology, 2020).

- Preidis GA et al. AGA Technical Review on the Role of Probiotics in the Management of Gastrointestinal Disorders (Gastroenterology, 2020).

- Guo Q et al. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhoea: systematic review and meta-analysis (Cochrane, 2021).

- Efficacy and safety of probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis (Clinical Nutrition ESPEN, 2024).

- Kato Y et al. Lactococcus lactis strain Plasma and common cold-like symptoms: individual participant data meta-analysis (Frontiers in Immunology, 2025).